Five Metrics to Reduce Financial Data Risk

Five Metrics to Reduce Financial Data Risk

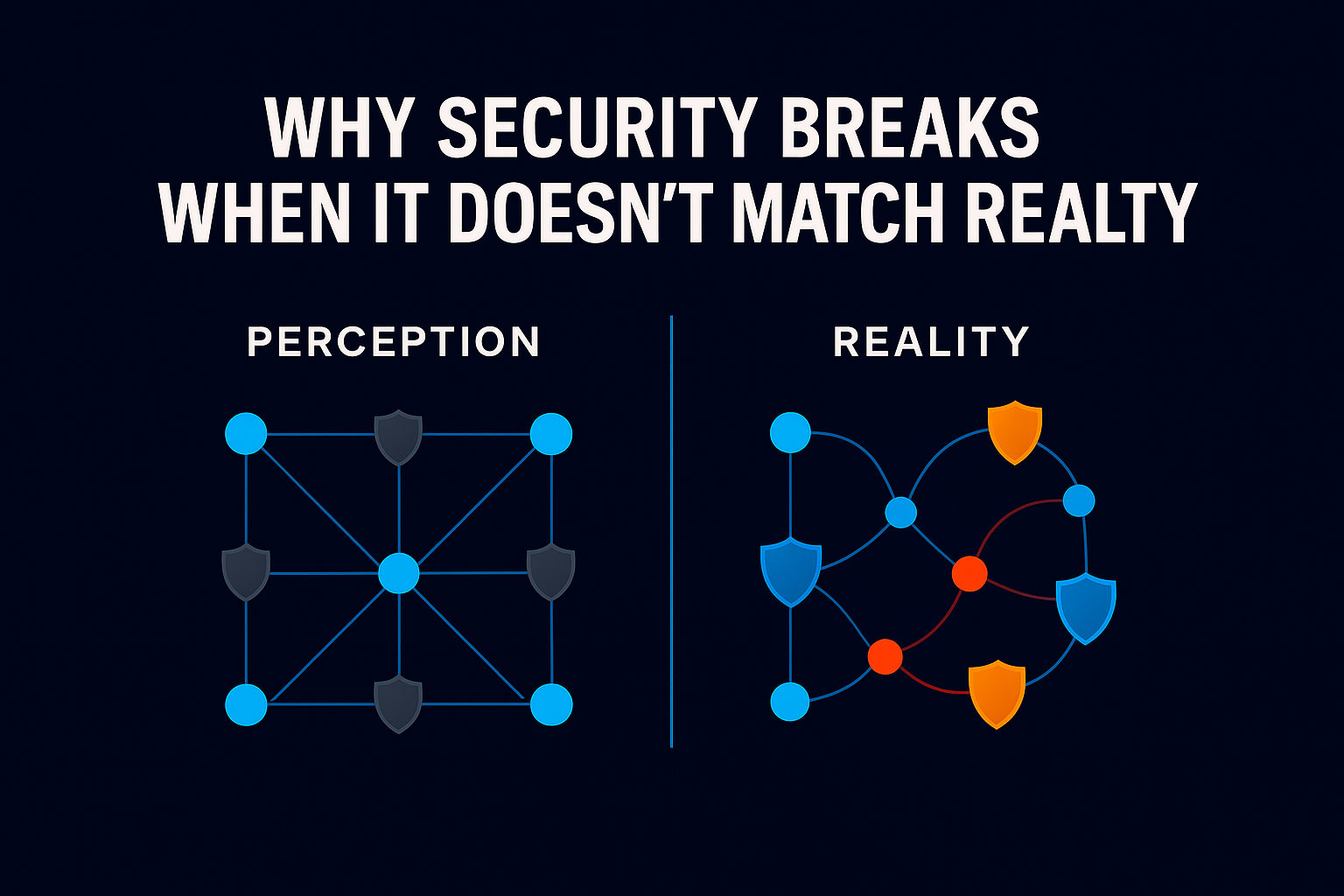

Financial institutions run comprehensive security programs, regular audits, access reviews, and controls testing. Yet when board members or regulators ask whether data risk is moving in the right direction, the answer often requires more explanation than it should.

The issue isn’t missing controls. It’s that most reporting focuses on whether access was approved and reviewed, not on what that access looks like in aggregate or how it changes over time. Those answers matter when you’re trying to understand actual exposure, especially as regulators like NYDFS tighten access management requirements and scrutiny intensifies around customer data protection.

Here are five signals that can help security teams measure and communicate data access risk more clearly.

1. Unused access to sensitive data

Access granted for legitimate reasons doesn’t always get removed when the work is done. A contractor finishes a project. An analyst moves to a different team. An audit wraps up. The permissions often stay.

This creates a growing inventory of access that serves no business purpose but increases impact if credentials are compromised. For financial institutions handling customer financial data, transaction records, and personal information under regulations like GLBA and state privacy laws, unused access represents pure risk with no operational upside.

The NYDFS amended cybersecurity regulation (23 NYCRR 500.7) now requires covered entities to periodically review all user access privileges, at minimum annually, and remove or disable accounts and access that are no longer necessary. Tracking unused access to regulated data shows where exposure can be reduced without affecting operations.

2. Number of identities with access to critical data

It’s useful to know how many people and service accounts can reach your most sensitive datasets: customer accounts, trading systems, core banking platforms, payment processing data.

This isn’t about questioning whether individual access decisions were correct. It’s about understanding scale. In financial services, where a breach triggers regulatory reporting requirements, potential litigation, and immediate reputational damage, risk correlates with how many identities have access to what matters most. The IMF’s April 2024 Global Financial Stability Report documents that cyber incidents have caused $12 billion in direct losses to financial firms over the past two decades, nearly one-fifth of all reported cyber incidents affect this sector.

Monitoring this number over time shows whether your blast radius is growing or shrinking, and whether your controls are actually reducing exposure or just documenting it.

3. Trend Lines, Not Snapshots

Security controls get implemented at specific moments. Risk accumulates continuously.

Showing whether data access exposure is increasing, stable, or decreasing gives leadership and regulators context that a list of controls can’t provide. For institutions subject to regular examinations, whether from the OCC, Federal Reserve, or FDIC, being able to demonstrate direction matters as much as the current state.

You don’t need sophisticated risk scores. Even a directional trend (e.g. access to customer financial data down 15% quarter-over-quarter, or service accounts with production access reduced by 20%) demonstrates that risk management efforts are working. For many CISOs, the question from the board or examiners isn’t “do we have controls?” It’s “are they making a measurable difference?”

4. Gap Between Granted Access and Actual Use

In most financial institutions, granted access grows faster than used access, sometimes dramatically so.

When that gap widens, it suggests that permission models are drifting from operational reality. People accumulate access over time through job changes, project work, mergers and acquisitions, and role evolution. But they don’t exercise most of it. The result is elevated exposure without corresponding productivity, and access reviews that validate permissions without any indication of whether they’re needed.

This pattern is particularly acute in financial services, where systems accumulate over decades, business lines maintain separate applications, and regulatory requirements make it difficult to simply turn things off. The result: permissions that were granted five years ago for a system that’s been replaced, but the access remains because no one wants to risk breaking something.

Viewed in aggregate, this metric explains why traditional access reviews often feel disconnected from real risk. Reviewers validate that someone “might need” access, but have no data on whether it’s ever used.

5. Where Visibility is Incomplete

No financial institution sees everything. But knowing where you can’t see clearly is a risk signal itself, and increasingly, a regulatory expectation.

Common blind spots: SaaS platforms outside centralized IAM (Salesforce, Snowflake, collaboration tools), service accounts running automated processes, data replicated into analytics environments, shadow IT, and third-party connections. NIST 800-53 controls CM-8 (System Component Inventory) and PM-5 (System Inventory) establish requirements for maintaining comprehensive asset inventories, a baseline expectation that many financial institutions adopt as part of their security frameworks. The CFPB’s Personal Financial Data Rights rule (Section 1033), finalized in October 2024, creates additional complexity around who can access consumer financial data and under what conditions.

Identifying these gaps helps you assess confidence in your overall posture and decide where to focus next, without rebuilding governance from scratch. For many institutions, the revelation isn’t that gaps exist, but rather how large they are.

Who Owns What

These signals aren’t meant to shift responsibility for access decisions to security leadership. Those decisions still belong with IAM teams, application owners, and business unit leaders who understand operational needs.

The value is in aggregation and communication. These metrics support board discussions, regulatory conversations, and internal oversight without pulling security leaders into operational access management. They answer the “so what” question that executives and examiners are actually asking.

Beyond visibility: continuous risk reduction

As financial institutions modernize platforms, adopt cloud infrastructure, and expand digital channels, understanding risk means more than knowing what access exists. It means continuously detecting when access drifts from operational need and responding automatically to reduce exposure.

Some institutions are moving beyond periodic access reviews to continuous monitoring and automated response, detecting when permissions haven’t been used in 90 days and flagging them for removal, identifying when service accounts receive access to customer data and requiring additional approval, or automatically revoking temporary access when project timelines expire.

This isn’t about adding more visibility dashboards. It’s about building systems that continuously reduce risk without requiring manual intervention for every decision. The institutions making progress here aren’t just measuring access patterns, they’re using those patterns to drive automated risk reduction while keeping critical work moving.

Regardless of tooling, grounding data security discussions in clear, measurable signals helps security leaders make better decisions, and explain them with confidence to the people who matter: boards, regulators, and examiners who want to understand whether risk is moving in the right direction.

Ray Security provides continuous detection and automated risk reduction for data access across cloud and SaaS, hybrid and on-prem platforms, helping financial institutions measure exposure and automatically respond without manual reviews. If you’d like to discuss how other financial institutions are approaching these challenges, reach out.